Emergency Action Message

An Emergency Action Message (EAM) is a highly structured, authenticated message primarily used in the command and control of United States military nuclear forces. These encoded alphanumeric messages are disseminated over multiple survivable communication systems including the High Frequency Global Communications System (HFGCS), VERDIN, and satellite systems, serving as the primary means of transmitting time-sensitive orders and information to U.S. strategic forces worldwide. Unclassified U.S. Department of Defense documents describe Emergency Action Messages are described as highly structured, authenticated messages primarily used in the command and control of nuclear force that are disseminated over numerous survivable and non-survivable communication systems, including terrestrial and space systems.[1]

Overview

EAMs are broadcast continuously across multiple high-frequency radio bands via the HFGCS, transmitted by ground stations worldwide and rebroadcast by airborne platforms including E-6B Mercury aircraft. The messages consist of alphanumeric character sequences transmitted via voice by radio operators, with each message preceded by a two-character prefix that serves as a classification indicator. Each message is read twice in its entirety for verification purposes, ensuring accurate reception by intended recipients across distributed strategic forces.

The HFGCS operates on primary frequencies of 4724, 8992, 11175, and 15016 kHz, with ground stations typically simulcasting messages across multiple frequencies simultaneously to ensure redundant coverage. The E-6B Mercury fleet, operated by Strategic Communications Wing 1, plays a critical role in the EAM system. The E-6B's primary mission is to "receive, verify and retransmit Emergency Action Messages (EAMs) to US strategic forces."[2] E-6B aircraft rebroadcast messages over HF as well on VLF frequencies by way of their trailing wire antenna, extending coverage to submerged submarines that cannot receive HF transmissions.

Message Structure and Format

All EAMs broadcast via the HFGCS follow a consistent transmission format that facilitates accurate reception and verification across geographically dispersed receiving stations. The standard broadcast format consists of four distinct phases. First, the operator provides a preamble identifying the transmission type and may include additional context such as message count or special handling instructions. Second, the operator announces the two-character prefix followed by the complete alphanumeric message content. Third, the message is read character by character in its first complete reading, with each character transmitted phonetically using standard military phonetic alphabet conventions. Fourth, the entire message is repeated in its entirety as a second reading for verification purposes, allowing receiving stations to confirm accurate transcription. This dual-reading protocol has been documented in multiple observations of HFGCS transmissions and serves as a standard error-checking mechanism for ensuring message integrity across long-distance radio communications.

Messages are composed from a restricted alphanumeric character set rather than the full range of letters and digits. The character set excludes the digits 0, 1, 8, and 9 almost entirely.[Note 1] The exclusion of 0 and 1 likely addresses the potential for visual confusion with the letters O and I respectively, a concern that remains relevant despite phonetic transmission because messages may be read from handwritten copies by operators.[Note 2] The exclusion of 8 and 9 is less immediately obvious from a readability perspective but becomes comprehensible when considering that the character set A through Z combined with digits 2 through 7 yields exactly 32 possible characters, suggesting the use of base-32 encoding in EAM encryption schemes. Each permitted character is transmitted phonetically using standard military phonetic alphabet conventions, eliminating ambiguity in radio reception even under degraded signal conditions.

The two-character prefix that precedes each message serves as a classification indicator, with different prefixes corresponding to different message categories. Analysis of HFGCS traffic patterns reveals that prefixes rotate on schedules independent of one another, with each message category using a single active prefix across the entire HFGCS network at any given time. Prefix rotation schedules vary by message category, with some prefixes remaining active for three to eight weeks before transitioning to a new prefix, while others show more sporadic appearance patterns. During transition periods, the new prefix typically appears simultaneously with the cessation of the previous prefix, indicating coordinated network-wide updates rather than gradual migration patterns.

Message Categories

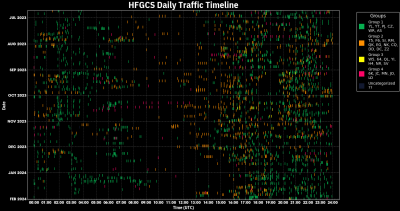

HFGCS monitors have identified four distinct categories of Emergency Action Messages based on consistent behavioral patterns observed in the two character prefixes that begin each message. These categories, designated Groups 1 through 4, are distinguished by analyzing how prefixes behave across monitoring data: certain prefixes consistently appear only on 30 character messages with no addressees (Group 1), others appear on variable-length messages often including addressee specifications (Group 2), still others cluster at specific shorter lengths with embedded character repetitions (Group 3), and a final category appears exclusively on extended-length messages with high prevalence of repeated character sequences (Group 4). Analysis of comprehensive monitoring data spanning June 23 2023 through February 01 2024 provides quantifiable documentation of their relative prevalence and observable characteristics, with these patterns remaining consistent across subsequent observations.[3]

Group 1 EAMs

Group 1 EAMs constitute the most common EAM type, accounting for approximately 66% of all EAM traffic observed during the reference period. Group 1 prefixes are identified by absolute consistency in message characteristics: every message with a Group 1 prefix measures exactly 30 characters in length without exception, and only a single Group 1 prefix is active across the entire HFGCS network at any given time. This structural uniformity makes Group 1 the most straightforward category to identify through pattern analysis of monitoring data.

Group 1 messages represent the most frequently rebroadcast message type within the HFGCS architecture. Individual Group 1 messages are often repeated dozens of times over periods spanning several hours, with both ground stations and E-6B aircraft participating in rebroadcast activities. E-6B platforms demonstrate strong preference for Group 1 content in their rebroadcast selections, with these messages comprising the majority of EAMs retransmitted by airborne platforms. This rebroadcast behavior suggests Group 1 messages serve operational purposes requiring broad dissemination and extended transmission windows to ensure reception by mobile or intermittently-available receiving stations.

Group 1 prefixes rotate on a regular schedule independent of other message categories. Observed rotation patterns indicate that Group 1 prefixes typically remain active for three to eight weeks before transitioning to a new prefix. These transitions occur at irregular intervals rather than on fixed calendrical schedules, suggesting that operational factors rather than predetermined timelines govern prefix rotation decisions. During transition periods, the new prefix typically appears simultaneously with the cessation of the previous prefix, indicating coordinated network-wide updates rather than gradual migration patterns.

Group 2 EAMs

Group 2 EAMs constitute approximately 26% of EAM traffic. Group 2 prefixes are identified through characteristic patterns that distinguish them from Group 1's uniformity: messages with Group 2 prefixes range from 30 to 163 characters in length, with the most common lengths being 30, 34, 35, 39, 51, and 55 characters. This length diversity distinguishes Group 2 prefixes from Group 1 prefixes, which appear exclusively on 30 character messages. Additionally, approximately 47% of messages with Group 2 prefixes include explicit "FOR [CALLSIGN]" addressee specifications, providing immediate identification of the Group 2 prefix when such messages are observed.

Messages with Group 2 prefixes that include addressee specifications are designated Directed EAMs and represent a distinct subcategory with well-documented callsign patterns. Documented addressee types include organizational designations (FORCE callsigns identifying entire command structures), geographic area designations (REGION callsigns specifying operational theaters), E-6B-associated numbered callsigns correlating with specific airborne platforms, and tactical word-only callsigns used for specialized recipient categories. The presence of explicit addressee specifications in these messages indicates targeted communication purposes requiring identification of specific receiving units, contrasting with the broadcast-to-all-stations approach characteristic of Group 1 messages.

The remaining 53% of messages with Group 2 prefixes are broadcast without addressee specifications, making them superficially similar to other message categories during individual transmissions. Reliable identification of Group 2 prefixes requires observation of prefix behavior over extended time periods, noting patterns such as variable message lengths or occasional appearance with addressee specifications. Like Group 1, Group 2 employs a single active prefix across the entire HFGCS network at any given time, with rotation occurring on an independent schedule separate from other message categories.

Group 3 EAMs

Group 3 EAMs constitute approximately 3% of EAM traffic. Group 3 prefixes are identified through distinctive length clustering and frequent appearance of embedded repeated character sequences. Messages with Group 3 prefixes show pronounced concentration at specific lengths, with 22, 27, 32, and 37 characters being most common and accounting for approximately 60% of all Group 3 traffic observed during the reference period. This clustering pattern distinguishes Group 3 prefixes from Group 2's broader length distribution and Group 1's rigid 30 character format.

Approximately 40% of messages with Group 3 prefixes contain repeated character sequences of three or more characters embedded within the message structure. These repeated sequences (such as "32R" appearing twice in different positions, or "COH" appearing three times throughout a message) provide a distinctive structural signature. This prevalence of internal repetition is nearly identical to that observed in Group 4 messages and significantly exceeds the repetition frequency found in Groups 1 and 2. The functional purpose of these repeated sequences remains unclear from external observation, but their consistent appearance suggests they serve structural roles within the message format rather than representing random encryption artifacts.

Group 3 prefixes show sporadic appearance patterns distinct from the relatively stable rotation schedules observed in Groups 1 and 2. Group 3 prefixes often appear for only a few days before disappearing for extended periods, sometimes vanishing for weeks or months before reappearing. However, sustained periods of elevated Group 3 activity have been documented, during which Group 3 prefixes appear with much greater frequency over consecutive days or weeks. These activity fluctuations suggest that operational factors influence Group 3 transmission frequency, with certain operational conditions or exercises triggering increased Group 3 usage.

Group 4 EAMs

Group 4 EAMs constitute approximately 3% of EAM traffic and represent the longest and most structurally complex EAM category. Group 4 prefixes are identified through their appearance on extended-length messages ranging from 36 to 292 characters, spanning nearly an order of magnitude in size variation. The most common Group 4 lengths are 142, 120, 164, 68, 50, and 216 characters, though the diversity of observed lengths indicates substantial format flexibility.

Approximately 60% of messages with Group 4 prefixes contain repeated single-character sequences of four or more identical characters (such as FFFF, XXXX, ZZZZ, RRRR), representing the highest prevalence of this repetition pattern across all EAM groups. Additionally, approximately 38% of Group 4 messages contain repeated multi-character sequences of three or more characters, similar to the pattern observed in Group 3 messages. The frequent appearance of these extended repetition patterns in messages with Group 4 prefixes suggests structural complexity beyond simple character-by-character encoding, potentially indicating message formats that include headers, delimiters, or embedded metadata fields.

Group 4 messages show the highest transmission error rate of any EAM category, a consequence of their extended length and structural complexity. Operators occasionally stumble over extended character sequences, restart readings when errors are detected, or experience fatigue-related mistakes during lengthy transmissions. Despite these challenges, the continued use of extremely long Group 4 messages indicates operational requirements that justify the increased risk of transmission errors inherent in complex message formats.

Structural Analysis

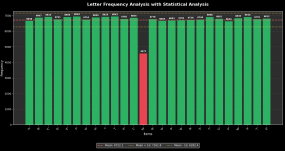

While the encrypted content of EAMs remains classified and inaccessible to external observers, analysis of large samples of EAM traffic reveals consistent observable patterns in character distribution, structural repetition, and message formatting. The statistical properties of the character sequences themselves exhibit characteristics that can be measured and analyzed through standard cryptographic analysis techniques.

Character frequency analysis performed on samples exceeding 6,000 unique EAMs demonstrates that the letters M and the digit 5 appear approximately half as frequently as other characters in the permitted character set.[4] This dramatic deviation from uniform distribution is statistically significant and suggests that the encryption algorithm or message structure systematically disfavors these characters. The mechanism producing this bias remains unclear, but possibilities include encryption schemes that map multiple plaintext inputs to single ciphertext outputs (with M and 5 representing less common output values), message structures that reserve these characters for special purposes, or encoding algorithms that inherently produce uneven character distributions. The consistency of this pattern across thousands of messages from different time periods and message categories indicates a fundamental characteristic of the EAM encoding system rather than a transient artifact.

Certain EAMs with identical two-character prefixes have been observed containing identical character strings within their message bodies, even when broadcast weeks or months apart.[5] This repetition of identical substrings across temporally separated messages with matching prefixes suggests that message formats may include fixed fields, headers, or structural elements that remain constant across messages of the same type. Such repetition would be incompatible with pure one-time pad encryption, which by definition produces unique ciphertext for every encryption operation and cannot generate identical outputs for different messages. The appearance of these repeated strings provides observable evidence that at least portions of some EAMs employ encryption methods other than one-time pads, or that certain message fields remain unencrypted.

Messages exceeding 100 characters in length frequently exhibit structural similarities based on specific message length, with repeated tetragrams (four-character sequences such as AAAA, BBBB, CCCC) appearing in similar positions across different messages of identical length.[6] This positional consistency of repeated sequences suggests that long EAMs employ structured message formats with designated field positions rather than treating the entire message as an undifferentiated block of encrypted data. Messages ranging from 30 to 100 characters also display structural patterns, though these patterns are often more subtle and require larger sample sizes to identify reliably. Even the structure of certain specific message lengths, such as 56 and 59 character messages, exhibits patterns that become apparent through comparative analysis, though the structural characteristics may be less immediately obvious than in longer messages.[Note 3][Note 4] Messages exceeding 200 characters show the most pronounced structural regularity, with format patterns often evident even from visual inspection of individual messages.

Encryption and Security

The encryption methods employed in Emergency Action Messages have been the subject of considerable speculation within the monitoring community and open-source intelligence analysis circles. The most commonly repeated claim asserts that all EAMs are encrypted using one-time pads (OTPs), a cryptographic method that provides theoretically unbreakable security when implemented correctly. However, this assertion lacks accessible source documentation, and several observable characteristics of EAM operations raise questions about whether one-time pad encryption is universally applied across all message categories.

One-time pad encryption requires that sender and receiver possess identical copies of random key material, with each character of the plaintext encrypted using a corresponding character from the key pad. The fundamental security property of OTP encryption demands that each portion of the key material be used exactly once and never reused, as reuse of key material creates vulnerabilities that can compromise security. For EAM operations, implementing universal OTP encryption would require distributing key material to numerous geographically dispersed receiving stations, including mobile platforms such as submarines, aircraft, and ground-mobile command posts. The volume of key material required would need to accommodate all messages that might potentially be transmitted during the operational period before key material can be refreshed, creating substantial logistical demands for key distribution and management.

The broadcast nature of HFGCS transmissions introduces additional complications for OTP implementation. Messages transmitted via the HFGCS are received simultaneously by multiple assets worldwide, including strategic bombers, ballistic missile submarines, command posts, and support facilities. The number and identity of receiving stations for any given message is not necessarily predetermined, as operational circumstances may require that messages reach assets whose operational status or geographic location was unknown at the time key material was distributed. The total volume of messages that will be transmitted during any given period is similarly unpredictable, as operational requirements drive message generation rather than predetermined schedules. These factors create key management challenges, as distributing sufficient key material to accommodate worst-case message volumes to all potential receivers while maintaining the security protocols necessary for OTP implementation represents a substantial logistical undertaking.

From a functional perspective, the operational requirements for EAMs may not demand the absolute cryptographic security provided by one-time pads. EAMs are time-sensitive messages whose operational relevance typically degrades rapidly after transmission, reducing the value of cryptanalytic efforts to decrypt aged traffic. The content of EAMs, even if successfully decrypted, would likely employ abbreviations, codewords, operation-specific terminology, and authentication elements that would be incomprehensible to unauthorized parties lacking the codebooks, authentication tables, and operational context necessary for interpretation. As long as EAMs employ encryption methods that resist real-time or near-real-time cryptanalysis using available computational resources, the practical security requirements for the system may be satisfied without requiring the theoretical perfection of one-time pad encryption. The trade-off between absolute cryptographic security and operational simplicity may favor encryption methods that provide high resistance to cryptanalysis while avoiding the key distribution and management complexities inherent in OTP systems.

This skepticism toward universal OTP usage may reflect the historical context in which assumptions about EAM encryption developed. The shortwave listening community largely emerged from monitoring numbers stations, many of which demonstrably employ one-time pad encryption based on cryptographic analysis of their transmissions. When the HFGCS became a subject of monitoring interest, observers familiar with numbers station operations may have assumed that EAMs similarly employed OTPs and this assumption became conventional wisdom through repetition rather than verification. The observable evidence discussed in the Structural Analysis section, particularly the appearance of identical character strings in messages with matching prefixes and the systematic structural patterns in long messages, provides grounds for questioning whether all EAMs employ pure OTP encryption or whether the encryption architecture varies by message type, content sensitivity, or operational context.

Transmission Patterns and Common Misconceptions

Analysis of EAM transmission patterns over extended monitoring periods reveals regularities in broadcast timing, frequency, and volume that contradict common assumptions about the operational significance of EAM traffic. Understanding these patterns and recognizing prevalent misinterpretations provides necessary context for assessing claims about correlations between EAM activity and geopolitical events.

EAM broadcast times are not uniformly distributed across the 24-hour cycle but instead show pronounced concentration during daylight hours for the continental United States.[7] This temporal clustering indicates that EAM generation and transmission correlate with normal working hours for command centers located within CONUS time zones rather than reflecting a continuously random operational tempo driven purely by real-time events. Certain days of the week exhibit consistently higher message volumes than others, with weekday patterns differing from weekend patterns in ways that suggest administrative and training schedules influence message generation alongside operational requirements.[8]

Daily EAM volumes observed over multi-year monitoring periods range from zero messages on certain days to more than fifty messages on others, with the typical range falling between five and twenty-five messages per day. Analysis of comprehensive monitoring periods provides more precise characterization of typical traffic levels: the June 23 2023 through February 01 2024 period averaged fourteen to fifteen messages per day with a median of fourteen,[9] while October through November 2024 and July 2025 showed slightly higher averages of eighteen to nineteen messages per day with medians of sixteen to seventeen messages.[Note 5] Days with exceptionally low traffic (zero to three messages) are relatively rare and tend to occur on federal holidays such as Thanksgiving and Christmas, further supporting the interpretation that routine EAM traffic correlates with normal duty schedules rather than continuous round-the-clock operational tempo. These baseline figures provide context for assessing whether any particular day's traffic volume represents a significant deviation from normal patterns.

Claims of correlation between EAM frequency and geopolitical events suffer from severe selection bias and lack statistical rigor. Observers frequently note apparent correlations when significant geopolitical developments coincide with days featuring more than two dozen EAMs, interpreting the elevated traffic as evidence of military response to current events. However, these same observers typically overlook days with thirty or more EAMs when no major news events occur, and conversely fail to comment on the absence of elevated EAM traffic during days with significant geopolitical developments. A rigorous correlation analysis requires comparing EAM volumes across all days regardless of news coverage, applying statistical methods to determine whether message volumes on days with major events differ significantly from baseline patterns. No such analysis has established a strong, consistent correlation between EAM broadcast frequency and geopolitical crises, military tensions, or international incidents.

The operational significance of long EAMs similarly requires careful analysis rather than assuming that message length correlates with importance or urgency. Monitoring data reveals that certain long messages appear with periodicity, with specific message lengths broadcast on recurring schedules that suggest planned transmissions rather than event-driven communications. Examples include 194 character messages broadcast on the third Sunday of consecutive months, with 219 character messages appearing the following day in both instances, and 246 character messages appearing in conjunction with 216 character messages on multiple Sundays.[10] Long messages appear more frequently on weekends than weekdays, consistent with scheduling patterns for exercises, training activities, or administrative procedures rather than crisis-driven operational traffic. If certain long messages are broadcast according to predetermined schedules with quasi-predictable timing, and geopolitical events do not exhibit comparable periodicity, then at least some long messages demonstrably do not correlate with real-world crises. Whether other long messages do correlate with operational events remains unresolved, but the existence of scheduled long-message traffic indicates that length alone does not reliably indicate operational significance.

Claims that HFGCS operators' vocal characteristics during EAM transmission provide indicators of message significance lack any credible foundation. These claims rest on the assumption that operators either understand the content of the messages they transmit or receive contextual information about operational significance, neither of which is established. More fundamentally, the track record of individuals making such claims demonstrates profound unreliability. Observers have claimed that operators were crying while reading EAMs that supposedly indicated imminent nuclear war, when subsequent analysis of the audio revealed the operator was laughing rather than crying and no crisis materialized. Operators may read practice messages with strong enunciation and slight vocal tension not because nuclear weapons are about to be employed but because supervisors are evaluating their performance and their career advancement depends on flawless execution. Like workers in any occupation, HFGCS operators' vocal characteristics may be influenced by personal circumstances, workplace dynamics, fatigue, humor, stress unrelated to message content, or any number of factors having nothing to do with the operational significance of the message being transmitted. Treating operator tone as an intelligence indicator represents speculation without evidentiary foundation.

Force Direction Messages

Force Direction Messages (FDMs) are rarely mentioned in publicly available Department of Defense documentation, though in the past they did appear occasionally alongside Emergency Action Messages in materials related to strategic communications and command and control systems. For example, a 1999 document describing the Single Channel Transponder System explicitly stated that the SCTS "provides Emergency Action Message (EAM) and Force Direction Message (FDM) dissemination capability" and identified FDMs as one of the survivable means of disseminating messages from the National Command Authorities.[11] However, whether FDMs survived as a distinct message category into the 2000s and beyond, and whether or not they remain part of current HFGCS broadcast traffic, is unclear from available materials. The paucity of contemporary references to FDMs contrasts with their documented role in late-Cold War strategic communications architecture and raises questions about whether the term has been superseded, whether FDMs have been integrated into the EAM classification system, or whether operational security considerations have simply reduced public discussion of this message type.

Analysis published by numbers-stations.com suggests that if FDMs do exist within current HFGCS traffic, they are likely structured similarly to EAMs, potentially making them difficult or impossible to distinguish from EAMs through external observation alone.[12] If external differentiation between EAMs and FDMs is genuinely impossible, the practice within the monitoring community of referring to all observed messages as "EAMs" may represent either accurate classification (if FDMs no longer exist as a separate category) or unavoidable imprecision (if FDMs do exist but cannot be identified from message structure). The inability to definitively resolve this question means that all analysis of "EAM" structure, patterns, and characteristics discussed in preceding sections could potentially apply to a mixed population of both EAMs and FDMs rather than to a pure sample of Emergency Action Messages, though without contemporary confirmation that FDMs remain operationally distinct from EAMs, this concern may be purely theoretical.

This ambiguity has practical implications for precise terminology. Discussion of HFGCS message traffic could reference "EAMs and/or FDMs" to acknowledge the uncertainty about which messages belong to which category. However, this formulation is cumbersome and pedantic, and colloquial usage within monitoring communities has established "EAM" as the standard term for all such messages regardless of their technical classification. This represents a case where conventional terminology has diverged from technical precision, and the colloquial term has achieved sufficient widespread adoption that insisting on the technically correct formulation would impede rather than enhance communication.

Despite the inability to distinguish EAMs from FDMs based on message structure alone, observable patterns suggest that certain message subgroups exist based on the two-character prefix system. Analysis of prefix usage over time reveals that messages can be categorized into distinct groups based on their first two characters, with these prefixes being reused over certain time periods but potentially acting as differentiating traits between message types.[Note 6] These prefix-based groupings align with the four-category taxonomy (Groups 1 through 4) discussed in the Message Categories section, suggesting that the prefix system may serve to differentiate between EAMs and FDMs, or to subdivide one or both message types into functional subcategories. While external observers cannot definitively determine which prefixes correspond to EAMs versus FDMs, the existence of systematic prefix-based categorization indicates that leads do exist for eventually differentiating these message types if additional information becomes available.

Historical Context and Documentation

Despite the unclassified status of the HFGCS itself, public documentation of Emergency Action Messages and the systems that transmit them has declined substantially since the mid-2000s. This reduction in publicly available information has created challenges for researchers and monitors seeking to understand system architecture, operational procedures, and the evolution of EAM formats over time.

Evidence indicates that, at least historically, EAMs were encoded using a program called EAMGEN (Emergency Action Message Generator).[13] This program is referenced in a 1999 glossary of SIOP-related terms published by the Natural Resources Defense Council, which defined EAMGEN in the context of nuclear war planning and strategic force communications.[14] Whether EAMGEN remains in use for current EAM generation or has been superseded by newer systems is not publicly documented, but the existence of a dedicated message generation program underscores the systematic, automated nature of EAM encoding processes rather than manual encryption by individual operators.

Declassified documentation provides rare glimpses into specific operational uses of EAMs during historical events. Transcripts of phone conversations from September 11 2001 archived by the Department of Defense reveal that an EAM was employed to change the DEFCON level in response to the terrorist attacks that day.[15][16] This documentation demonstrates that EAMs serve as the mechanism for transmitting fundamental changes in force posture and alert status, confirming their role as primary command and control tools for strategic force management during crisis conditions.

Larry Van Horn's 2006 documentation of the HFGCS remains the most comprehensive publicly available technical description of the system and is widely cited in subsequent analyses, though portions of this documentation have become outdated as system architecture and operational procedures have evolved over the intervening years. Contemporary descriptions of the HFGCS appear in Department of Defense budget justification documents, which provide high-level descriptions of system capabilities and modernization efforts, but these sources are less accessible than dedicated technical documentation and typically lack the operational detail found in earlier public sources.[1]

The HFGCS maintained a public website during the 1990s that provided information about system operations, personnel, and capabilities.[17] The Air Force published articles about HFGCS operations through 2006, including features on radio operators and system capabilities, providing accessible public information about this component of strategic communications infrastructure.[18] Such official disclosures have become increasingly rare in subsequent years, with the Air Force and Navy providing minimal public information about current HFGCS operations despite the system's unclassified status. This trend toward reduced transparency has shifted the burden of documenting HFGCS operations to independent monitors and open-source researchers rather than official channels.

Network Operations

The HFGCS ground station network consists of transmitter sites distributed globally to ensure redundant coverage across all geographic regions where U.S. strategic forces operate. Ground stations are remotely controlled from Centralized Network Control Stations, with control facilities documented at Joint Base Andrews and Grand Forks Air Force Base. Offutt Air Force Base was previously identified as having or developing control capabilities, though the operational status of these facilities may have been affected by severe flooding that damaged portions of Offutt AFB in 2019.

Ground stations typically simulcast EAMs across all four primary HFGCS frequencies (4724, 8992, 11175, and 15016 kHz) simultaneously, ensuring that receivers can maintain contact on at least one frequency despite propagation conditions that may render other frequencies unusable at particular times or locations. However, single-frequency transmissions also occur, particularly when messages are directed to specific geographic regions where propagation analysis indicates that a single frequency will provide optimal coverage. Historical documentation suggests that the HFGCS operates according to predetermined frequency schedules that optimize coverage based on time of day, season, and solar activity levels, though current scheduling practices are not publicly documented in detail.

E-6B Mercury aircraft serve dual roles as both EAM receivers and rebroadcast platforms, providing airborne communication nodes that extend coverage to areas not adequately served by ground stations and ensuring continuity of communications even if ground infrastructure is degraded or destroyed. According to official documentation, the E-6B's primary mission includes receiving, verifying, and retransmitting Emergency Action Messages to U.S. strategic forces. When an E-6B rebroadcasts EAMs on HF frequencies, the aircraft selects messages from the accumulated traffic it has received from ground stations and other airborne platforms, with analysis of rebroadcast patterns showing strong preference for Group 1 messages. The criteria governing message selection for rebroadcast are not publicly documented, but the preferential treatment of Group 1 messages suggests that this category serves operational purposes requiring maximum dissemination and extended transmission windows. The same E-6B may simultaneously operate on VLF frequencies using its trailing wire antenna system, rebroadcasting messages to submerged submarines that cannot receive HF transmissions while submerged but can receive VLF signals through their extremely low frequency communication systems.

Monitoring and Analysis

EAMs are monitored by radio enthusiasts, researchers, and open-source intelligence analysts worldwide, facilitated by the unclassified nature of HFGCS transmissions and the accessibility of equipment capable of receiving HF radio signals. Online communities track EAM traffic, document message patterns, maintain databases of observed transmissions, and collaborate on analysis of structural characteristics and transmission patterns. Projects such as the NEET INTEL DAILY TIMECARD PROJECT have compiled extensive records of EAM traffic over multi-year periods, creating datasets that enable statistical analysis of message patterns, prefix rotations, transmission frequencies, and temporal distribution of traffic.

Software-defined radio technology and web-based receivers have democratized access to HFGCS monitoring, eliminating the need for specialized radio equipment and making real-time observation accessible to anyone with internet connectivity. Services like WebSDR provide browser-based interfaces for tuning to HFGCS frequencies and listening to live transmissions from receiving stations located around the world, enabling global audiences to monitor EAM broadcasts and verify claims about transmission patterns and message characteristics. This technological accessibility has expanded the monitoring community beyond traditional shortwave listening enthusiasts to include researchers, students, journalists, and curious observers who can now access strategic communications monitoring without investment in radio hardware.

While the encrypted content of EAMs remains classified and inaccessible to external observers, structural analysis of message formatting, categorization, and transmission patterns has revealed significant observable characteristics that inform understanding of HFGCS architecture and operational usage. The four-group taxonomy documented in the Message Categories section, the prefix rotation schedules, the addressee patterns in Directed EAMs, the embedded structural features in long messages, and the temporal patterns in transmission timing all represent characteristics that can be measured, quantified, and analyzed through sustained observation despite the encryption protecting message content. These observable patterns provide insights into how the EAM system categorizes and transmits different types of traffic, even though the actual orders, information, and authentication data contained within the messages remain secure.

See also

Notes

- ↑ For almost all messages broadcast over the HFGCS (8888 messages are an exception), the characters 0, 1, 8, and 9 don't appear in them. Where they do appear in standard EAMs, it's extraordinarily rare and suspected to result from errors and/or message tests.

- ↑ We've previously heard HFGCS operators complain about the quality of message handwriting; https://x.com/neetintel/status/1736431126208512360

- ↑ The apparent structure of 56 character messages is, by comparison, more obscure; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xGA_IB5ruyc

- ↑ ChatGPT v3 helped identify the structure of 59 character messages; https://x.com/neetintel/status/1732568663838904474

- ↑ The June 2023-February 2024 period represents 224 days of monitoring, while the October-November 2024 and July 2025 periods represent 61 and 31 days respectively. The higher averages in later periods may reflect seasonal variation, evolving operational patterns, or statistical variation due to smaller sample sizes.

- ↑ The NEET INTEL HFGCS Report for November 2023 split EAMs into four discrete groups based on their first two characters; https://x.com/neetintel/status/1731808435744784412

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 (FY) 2024 Budget Estimates, Justification Book Volume 1 of 1, Other Procurement, Air Force, Department of Defense, (PDF), 2023-03.

- ↑ Strategic Communications Wing 1, airpac.navy.mil.

- ↑ NEET INTEL DAILY TIMECARD PROJECT (Part 1), June 23 2023 through February 01 2024.

- ↑ https://x.com/neetintel/status/1951159461089075651, @neetintel Twitter post, 2024-01-28.

- ↑ https://x.com/neetintel/status/1683976792703467520, @neetintel Twitter post, 2023-07-25.

- ↑ https://x.com/neetintel/status/1703141877627691399, @neetintel Twitter post, 2023-09-16.

- ↑ https://x.com/neetintel/status/1732104017759654052, @neetintel Twitter post, 2023-12-05.

- ↑ https://x.com/neetintel/status/1726650967771283922, @neetintel Twitter post, 2023-11-20.

- ↑ NEET INTEL DAILY TIMECARD PROJECT (Part 1), June 23 2023 through February 01 2024.

- ↑ https://x.com/neetintel/status/1726650967771283922, @neetintel Twitter post, 2023-11-20.

- ↑ Single Channel Transponder System (SCTS) (U), GlobalSecurity.org, 1999.

- ↑ The HF-GCS and Emergency Action Messages, The Number Stations Research and Information Center, 2022.

- ↑ https://x.com/neetintel/status/1684008070484045824, @neetintel Twitter post, 2023-07-25.

- ↑ The Post Cold War SIOP and Nuclear Warfare Planning: A Glossary, Abbreviations, and Acronyms, William M. Arkin and Hans Kristensen, Natural Resources Defense Council, (PDF), 1999.

- ↑ https://x.com/ReidDA/status/1713272506394513818, @ReidDA Twitter post, 2023-10-14.

- ↑ Air Threat Conference and DDO Conference, U.S. Department of Defense, (PDF), 2001-09-11.

- ↑ HF Global Communications System Website (archived), 1997-03-19.

- ↑ Andrews radio operators assist crewmembers worldwide, Joint Base Andrews, 2006.